I was halfway through my second season of coaching middle school soccer when, after the full-time whistle, one of my players kicked an opponent in the shin—right in front of the referee.

The ref, unsurprisingly, immediately showed him a red card.

When we regrouped, my players told me the other team had been talking trash the entire match. One had even told my player he was going to fuck his mother. Yet, no punishment was given for that. My player, usually a quiet and easygoing kid, may have snapped, but to him, it probably felt like the only fair response (to be honest, after hearing the things they were saying, I kind of wanted to kick the kid too.)

But the real problem wasn’t his temper—it was his failure to operate outside of surveillance. His tactic was ineffective because he acted within view of the referee—the official surveillant of the game. The ref didn’t hear the insults, didn’t consider the buildup, and didn’t care about the provocation. He only saw the reaction, and enforced the rules accordingly.

For most of football history, players bent the rules in the blind spots of officiating, exploiting the natural limitations of human perception—as Michel de Certeau might put it, a victory of time over space.

But what happens when there are no more blind spots and every moment is recorded, slowed down, and re-examined? This is the world VAR has created. And just like in everyday life, when institutions expand surveillance and tighten control, people (and players) find new ways to make use of the system.

Pre-VAR Tactics

Football used to thrive on moments of invisibility, where quick thinking and subtle deception could create an edge.

This is what Michel de Certeau calls tactics—improvised actions taken by those without power to navigate the rules imposed by those in control. Strategies, by contrast, belong to institutions. They set the boundaries; tactics find ways to work within (or around) them.

Before VAR, football was a tactician’s playground. Players didn’t just follow the rules—they made use of them:

- Diving & Simulation: A well-executed dive could win a penalty. The best divers knew exactly how to fall just believably enough, making sure the referee’s angle worked in their favor.

- Off-the-Ball Fouls: A shirt pull just outside the referee’s line of sight could stop an attack without consequence.

- Time-Wasting & Gamesmanship: Goalkeepers faked confusion, defenders took their time on free kicks, and substitutions happened at a glacial pace when a team was ahead.

- Psychological Manipulation: Players surrounded referees to influence decisions, knowing that pressure—especially in a noisy stadium—could sway a ref’s judgment.

All of these were tactical responses to the limitations of human perception—they weren’t just breaking the rules; they were making use of the system as it existed to create an advantage.

Strategies in Everyday Life

But De Certeau’s idea of tactics vs. strategies doesn’t just apply to football—it’s about how people navigate systems designed to control them.

In The Practice of Everyday Life, de Certeau examines how consumers tactically operate within the strategic design of a supermarket. Grocery stores are carefully planned to guide customers into making certain choices:

- Essential goods like milk and bread are placed at the back, forcing shoppers to walk through aisles filled with tempting products.

- High-margin items are positioned at eye level, while cheaper alternatives are harder to find.

- Checkout lanes are lined with impulse buys, designed to take advantage of last-minute decision-making.

Tactics in Everyday Life

However, shoppers aren’t passive participants in this system. They develop tactics to work around these strategies, such as:

- Creating shopping lists to resist impulse purchases.

- Memorizing store layouts to move efficiently, bypassing unnecessary aisles.

- Choosing self-checkout to avoid cashier upselling and long lines.

- Exploiting pricing loopholes, like price-matching policies or finding misplaced markdown items (for example, extreme couponers)

This is because, as Michel de Certeau argues, people aren’t passive recipients of imposed structures—they actively reinterpret and manipulate them for their own purposes. He refers to this concept as “la consommation productive” (productive consumption).

Institutions design systems with a specific intended function, but individuals consume them in ways that subvert or reshape their original purpose. This idea is central to de Certeau’s argument in The Practice of Everyday Life:

- Reading a book isn’t passive—readers interpret, imagine, and impose their own meaning beyond the author’s intent.

- Walking through a city isn’t passive—pedestrians carve their own paths, cut through alleys, and repurpose urban spaces in unintended ways.

- Consuming media isn’t passive—viewers remix, parody, or apply content in unexpected ways that shift its meaning.

This is exactly how footballers operated in the pre-VAR era. The referee’s authority was a structured system, but players found gaps, shortcuts, and opportunities to subvert that structure for their own advantage.

However, as technology evolves, tactics change.

Football Surveillance’s Watershed Moment

Zidane’s 2006 World Cup final red card was football’s first true moment of technological enforcement, a turning point where recorded evidence overruled the limits of human perception.

Reports suggest the fourth official saw the replay on the stadium’s big screen—something completely unauthorized at the time. Zidane wasn’t punished based on what was witnessed in real-time. He was punished because technology expanded the surveillable space.

Much like how governments expanded surveillance after 9/11 (this was just the second World Cup since the incident), FIFA had discovered a new tool for control. The logic was the same: if the footage exists, it will be used. What was once unseen could now be reviewed, rewound, and retroactively punished.

Think about traffic cameras. Before, if you ran a red light and no cop saw it, you got away with it. Now, a camera records your plate, and you receive a fine in the mail days later. The act remains the same—only the mechanism of enforcement has changed.

Or consider workplace surveillance. Once, employees could take a slightly longer break or browse the internet for a few minutes unnoticed. Today, productivity tracking software logs every keystroke, security cameras watch break rooms, and managers can retroactively check digital records to enforce rules that once relied on real-time oversight.

A decade later, VAR would formalize this shift.

VAR Enters & Players Adapt

FIFA framed VAR as a tool for fairness, a way to eliminate referee mistakes and ensure justice on the pitch. But VAR also transformed football into a panopticon.

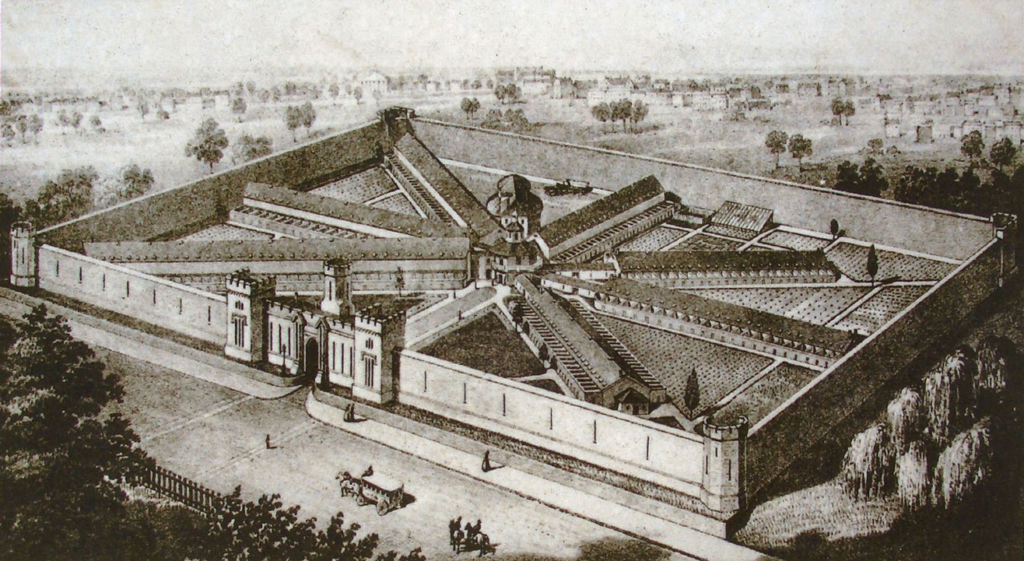

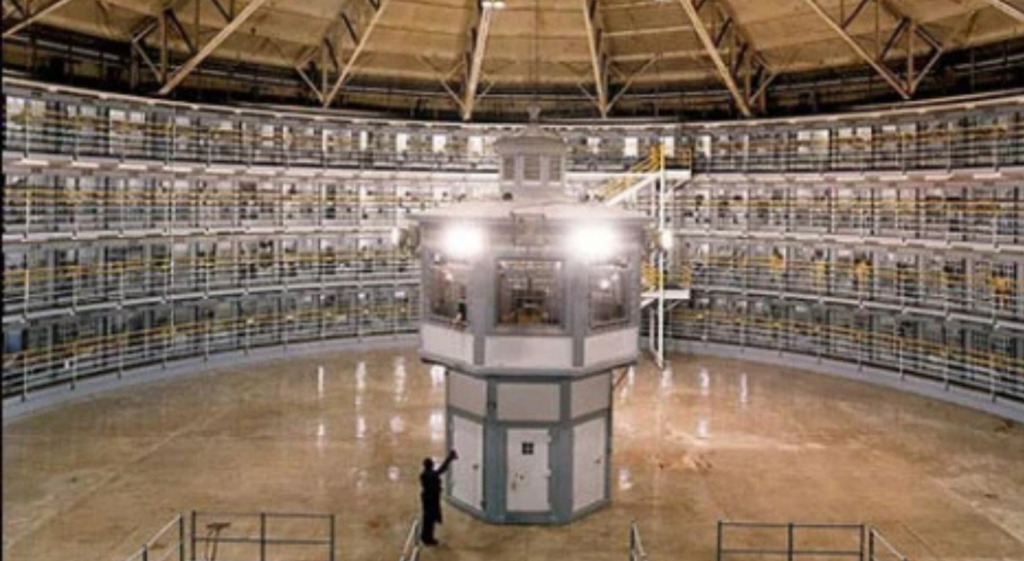

The panopticon, as conceived by philosopher Jeremy Bentham and later expanded upon by Michel Foucault, is a system of total surveillance where the watched can never be certain when they are being observed. In Bentham’s prison design, a single guard in a central tower could see every inmate, but the prisoners could never see the guard. The mere possibility of being watched was enough to make them regulate their own behavior.

VAR functions the same way.

Where tactics once relied on the limits of human perception, VAR promised total visibility—every goal, foul, and offside could now be re-examined from multiple angles. This shift mirrors what Michel de Certeau describes in The Practice of Everyday Life when he contrasts the lived experience of walking through a city with the detached view from above.

- From the top of a skyscraper, the city appears orderly, mapped, and controllable—a totality that can be studied, analyzed, and directed from a distance.

- But for the people on the ground, the city is a maze of shifting pathways, hidden shortcuts, and unpredictable encounters.

This is the transformation VAR introduced to football. Before, referees were on the ground, making calls in real-time, responding to the flow of play as they saw it. Now, officiating has been elevated to the aerial perspective—replays allow officials to pause time, zoom in, slow down frames, and analyze plays as if football were a fixed object rather than a fluid, unfolding event.

Just as city planners impose structure from above while pedestrians carve their own tactical routes below, VAR imposes a strategic, all-encompassing gaze on a game once governed by on-the-ground interpretation.

Althusser and Interpellation

Surveillance in football, as well as everyday life, doesn’t just enforce rules—it changes how people behave. This is what Louis Althusser calls interpellation—the moment a subject recognizes they are being watched and begins to conform to the expectations of authority.

For example, security cameras don’t just catch crimes—they change how people behave. When you know you’re being watched, you hesitate, self-police, and second-guess actions you once performed freely. A security camera doesn’t just record someone jaywalking—it makes them stop before they even consider crossing the street. Likewise, VAR doesn’t just review offside calls—it makes attackers hesitate before making a run.

Tactical Adaptations Under VAR

The more we’re watched, the more we internalize the expectation of surveillance. But surveillance doesn’t eliminate resistance—it forces adaptation. Footballers under VAR operate the same way. They don’t simply obey the new system—they actively reshape how it works by playing within and against it.

Surveillance was supposed to end tactical exploitation, but instead, it has created new loopholes, new spaces for manipulation. Players have learned to consume VAR on their own terms.

- The Slow-Motion Foul: A light touch in real time might not seem like much. But in slow motion, every movement looks exaggerated. Players now sell contact differently, knowing that a VAR review makes even minor fouls appear more deliberate.

- Offside By Design: Attackers no longer just focus on beating defenders. They also manipulate the lines VAR will draw. Some strikers now hold their runs for an extra fraction of a second, understanding that even a millimeter offside call can overturn a goal.

Tactical Adaptations in Everyday Life

VAR didn’t eliminate deception in football. It simply shifted where and how it happens.

Just like in everyday life, surveillance doesn’t mean total control. People adjust, adapt, and find ways to move within the system:

- Censorship leads to coded language.

- Facial recognition leads to disguises.

- Algorithms shape what we see online—but people learn to work around them.

In football and in life, tactics never disappear—they just evolve.