To most, Morrissey’s waving of the Union Jack during his performance of “Glamorous Glue” was something of a heel turn—he supposedly betrayed his fans by waving around a symbol that, at the time, was largely associated with Skinheads and the far-right. But this reading ignores what was really happening.

Morrissey wasn’t appealing to the Skinheads—he was taunting them. He was reclaiming British identity from those who had co-opted it for xenophobia.

From Controversy to Cool Britannia

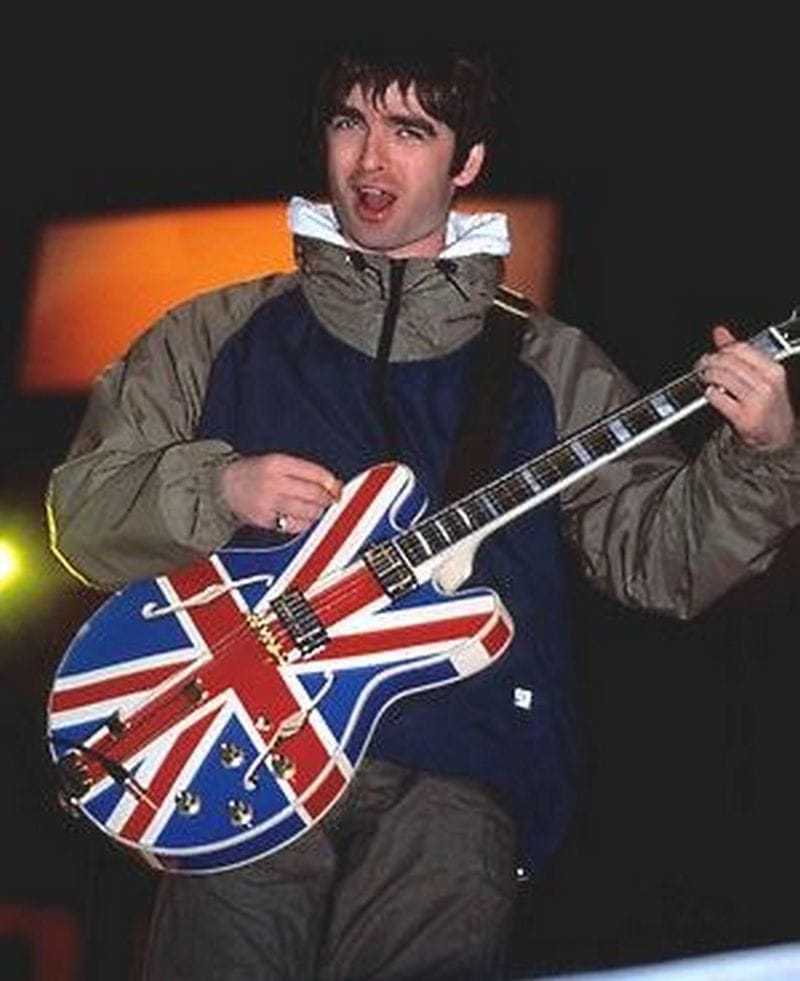

A few years later, the Union Jack was fully reabsorbed into mainstream British culture. The rise of Cool Britannia saw the flag embraced with a new, ironic, and celebratory energy—Noel Gallagher’s Union Jack guitar, Geri Halliwell’s iconic Union Jack dress, and a general aesthetic revival of British cultural pride.

While I hesitate to alienate my audience by quoting Joe Rogan, one of his stand-up jokes (2:30) encapsulates this kind of cultural reappropriation well:

If the gay folks decided to attack duck hunting, they could fuck it up pretty quickly… If I was the strategist for the gay community… I’d be like, ‘Here’s what we’re gonna do: From now on, you’re gonna do all your gay porn in camo… All you have to do is have a unified front–agree to that and they would win. They would take that shit over–the same way they took over the rainbow. THEY OWN THE FUCKING RAINBOW, IT’S THEIRS!”

It’s a similar principle—taking back symbols long claimed by regressive forces and flipping their meaning.

The Political Illusion of Cool Britannia

But Cool Britannia wasn’t just about pop culture—it infiltrated politics. Tony Blair and New Labour rode the wave of this cultural moment, branding themselves as the party of modern Britain. However, as Jarvis Cocker of Pulp pointed out in “Cocaine Socialism”, it was all just a performance.

New Labour wasn’t the working-class savior it pretended to be—it was a rebrand, not a revolution. It co-opted the language of progress while leaving the structures of power intact.

However, that doesn’t mean there’s nothing to learn from Cool Britannia—it showcased the power of national identity and nostalgia.

Nationalism Isn’t Optional—So It Must Be Reclaimed

Many people assume nationalism is something that can just be opted out of. But national identity is a powerful ideological force—even those who consider themselves anti-British (or anti-nationalist in general) still frame their identity in relation to nationality.

We don’t get to choose whether or not national identity affects us—it’s embedded in real-world structures. Passports dictate where we can travel. Citizenship defines our legal rights. Borders shape global politics.

So the only real option is to co-opt it.

Progressive movements shouldn’t cede national identity to conservatives and far-right reactionaries. If they don’t take control of the narrative, others will.

Utopia Isn’t a Dream—It’s a Strategy (feat. Fredric Jameson)

Fredric Jameson, in An American Utopia, argued that the Left’s biggest mistake is its allergy to power. We’ve become so skeptical of state institutions that we’ve forgotten how to repurpose them. Instead of abolishing power, we need to reclaim it—structurally, symbolically, and institutionally.

This is the same move Morrissey makes when he waves the Union Jack—not an embrace, but a détournement. Not a nationalist, but someone aware that nationalism is too powerful to ignore.

Jameson proposes something even more radical: universal conscription into a civic army—not for warfare, but for infrastructure, education, and care. In his vision, the only way to change the system is from within its structures, by transforming them into vehicles for equality and solidarity.

That’s the lesson here. If national identity is inevitable, then it can’t be left to the reactionaries. We must wrestle the flag away from the fantasy, even if that means playing with the very symbols we once feared.

Both Morrissey and Jameson show us that symbols—whether it’s a flag or the idea of the military—are empty signifiers. They gain meaning only through how they’re used. And if we don’t use them, someone else will. The universal army is not a call to arms, but a call to collectivity.

The only way to end the fantasy is to perform it better than the people who wrote the script.

Confronting the Conservative Fantasy

This approach also forces conservatives to face the contradictions of their own ideology. They can either:

- Cling to their nationalist identity while conforming to progressive values to keep it relevant.

- Admit that their nationalism was never really about history or national pride—it was always about fetishizing a past that never existed.

Morrissey’s waving of the Union Jack wasn’t a betrayal—it was a dialectical challenge.

An Anthology of Morrissey’s “Progressive Nationalism”

Morrissey’s approach to lyricism generally aligns with the trajectory of radical leftist thought over the past 40+ years:

- 1980s – Situationism & The Smiths Era: Rooted in detournement, pulling from Debord and the Situationist critique of the spectacle. He embraced working-class aesthetics, but detached them from their traditional political meanings, turning them into something romantic and tragic.

- 1990s – Political Subversion via Nationalism: Starts playing with nationalist symbols, knowing full well they carry an ideological charge. This is early Žižekian territory—playing with ideology, forcing the audience to confront its absurdity.

- Late 90s – Hopelessness, Disillusionment (Post-New Labour Realism): The Maladjusted era is post-New Labour disappointment—the realization that even the “progressive” alternative is an ideological trap. This aligns with Jameson’s postmodernism, where there’s no clear “outside” to ideology anymore.

- Mid-2000s-Late-2010’s – Full Žižekian Critique of Ideology: This is where Moz starts explicitly recognizing ideological structures.It’s beyond subversion—it’s ideological awareness.

- Potentially 2024+ (Bonfire of Teenagers – A Move Toward Badiou?): If Bonfire really leans into Badiou, we could be looking at a full break with ideological despair and a turn toward the Event. This could mean Moz starts searching for the Truth beyond ideological entrapment—something genuinely outside capitalism’s symbolic order.

Margaret on the Guillotine (1988): The Death of Thatcherite Britain

If there’s one thing I’m fairly certain Morrissey isn’t, it’s a Thatcherite. Few songs in his discography make his political contempt as explicit as Margaret on the Guillotine, the closing track of his debut solo album, Viva Hate.

The lyrics don’t just criticize Margaret Thatcher—they fantasize about her execution, framing it as a collective dream of the “kind people”:

“The kind people

Have a wonderful dream

Margaret on the guillotine“

Unlike much of Morrissey’s lyricism, which relies on irony, ambiguity, and clever wordplay, this song is blunt force trauma. There’s no romanticizing, no layered interpretation—just rage, an unmistakable wish for the destruction of Thatcherite Britain.

Thatcherism as the Death of Britain

Morrissey’s hostility toward Margaret Thatcher was shared by much of the working class, the artistic community, and the leftist opposition in the UK. Thatcher’s government was synonymous with:

- The decimation of British industry: Closing mines, weakening trade unions, and dismantling working-class job security.

- The privatization of public services: A shift from collective welfare to capitalist individualism.

- The destruction of British identity: (the version of Britain that was built around working-class solidarity, public institutions, and a cultural identity rooted in labor movements.)

For Morrissey, Thatcherism represented a betrayal of Britain itself—not just an economic or political shift but an existential rupture. The Britain he romanticized—one of Northern grit, working-class community, and national pride untangled from imperialist nostalgia—was being replaced by cold, neoliberal individualism.

This is what makes Margaret on the Guillotine a nationalist song—but not in the reactionary sense. It’s nationalist in that it expresses a longing for a Britain that once existed (or that should have existed). It’s the nationalism of the betrayed—a nationalism rooted in opposition to the ruling class rather than in support of it.

The Guillotine as a Revolutionary Fantasy

The French Revolution imagery is key here. The guillotine wasn’t just a tool of execution—it was a symbol of class vengeance, of the people reclaiming power from an out-of-touch elite. By invoking it, Morrissey aligns himself with revolutionary violence, even if it’s ultimately more theatrical than literal.

And yet, despite its provocative nature, the song’s melancholic tone suggests something more than just bloodthirsty anger—it suggests desperation, exhaustion, a Britain that has been drained of hope:

“And people like you

Make me feel so old inside

Please die“

This isn’t just about Thatcher—it’s about what she represents. Margaret on the Guillotine mourns the loss of a Britain that could have been saved, but wasn’t.

Morrissey, Nationalism, and the Police

The song’s infamy wasn’t just limited to public backlash—Morrissey was actually questioned by the police after its release. In an era where the British state was cracking down on dissent—whether from miners, Irish nationalists, or anti-Thatcher artists—a song like this was enough to raise state paranoia.

This raises an important question: Why does the British state see threats to its ruling class as threats to the nation itself?

- The police didn’t investigate this song because it posed a real danger—it was investigated because it challenged the authority of the state itself.

- This reinforces the conservative stranglehold on national identity—to be truly British, one must support the government, the monarchy, and the economic order.

- In this sense, Morrissey’s nationalism is deeply anti-government, positioning itself against the ruling elite, not alongside it.

Conclusion: Nationalism as Rebellion

While Thatcher and her supporters wrapped themselves in the Union Jack, Morrissey’s nationalism is a rejection of their Britain. Margaret on the Guillotine represents a nationalist longing for a Britain that values its people over its leaders, its history over its corporations, its culture over its capital.

Morrissey wasn’t singing about killing a person—he was singing about killing an ideology. And in doing so, he forces us to ask: What does it mean to love a country that doesn’t love you back?

Glamorous Glue (1992): Nostalgia, Capitalism, and the Death of England

If Margaret on the Guillotine was an explicit call for revolution, Glamorous Glue is something more philosophical, more existential, yet just as damning in its critique of modern Britain. While it might read like a lament for a dying England, it’s also a critique of capitalism, alienation, and the commodification of culture—a clear plea for something that, at its core, is communist-esque.

Everything of Worth Should Be Shared

Everything of worth

On Earth

Is there

To share

This is Morrissey’s most explicitly anti-capitalist statement. It cuts straight to the heart of class struggle—wealth and resources should not be hoarded, but shared. There is no metaphor here, no irony, no ambiguity. It’s a simple rejection of ownership, privatization, and inequality.

- It’s anti-individualism → The line dismisses the Thatcherite idea that “there’s no such thing as society.”

- It’s anti-elitism → If everything is to be shared, the very concept of class division is illegitimate.

- It’s anti-capitalist realism → Morrissey presents the most basic moral truth as if it should be obvious, but in doing so, exposes just how far modern Britain has drifted from it.

The Death of English Culture

From there, Morrissey moves into something even more damning—a diagnosis of cultural decay:

I used to dream, and I used to vow

I wouldn’t dream of it now

This isn’t just personal—it’s societal. Britain used to dream, used to aspire, used to imagine something better. But under capitalism—under the weight of image-driven consumer culture—those dreams have been replaced by cynicism, isolation, and empty spectacle.

We look to Los Angeles

For the language we use

London is dead, London is dead

This isn’t just about American cultural influence—it’s about the colonization of British identity by images, media, and fantasy. Real material culture has been replaced by its simulation—TV, Hollywood, advertising.

English culture isn’t dying from external attack—it’s dying from within. It no longer belongs to the people; it belongs to corporate interests, global capital, and media conglomerates.

Even language itself is being shaped by this takeover—not just in an aesthetic sense, but in a deeper, ideological sense. The way people speak, think, and even imagine their futures is dictated by American mass culture.

This ties into Žižekian ideology critique—how capitalist realism sustains itself by dictating what is even conceivable. If all dreams must be mediated through Hollywood, through commodity culture, then real political or social change becomes unimaginable.

Dwyer’s “Back to the Fifties” Nostalgia vs. Morrissey’s Nostalgia

As Michael Dwyer explores in Back to the Fifties, nostalgia is never really about returning to the past, but about constructing a fantasy of the past to serve present ideological needs. In postwar America and Britain, the 1950s were rebranded as an ideological safe haven—a mythical era of national strength, moral clarity, and cultural unity.

- Conservative nostalgia is performative—it sanitizes history, erasing its struggles to create a mythical “golden age” that serves modern reactionary politics.

- Cool Britannia nostalgia (in the 1990s) was a neoliberal branding exercise—it repackaged Britishness into something marketable and ironic, stripping it of any radical political potential.

- Morrissey’s nostalgia, however, isn’t about mythologizing the past in the same way—it’s about mourning a real material loss. He isn’t longing for empire or monarchy—he’s longing for a Britain that belonged to its people, before it was hollowed out by capital.

But here’s the problem: even if his nostalgia is rooted in class struggle, it still functions in a similar way to other ideological narratives.

He presents pre-Thatcher Britain as something pure, a place where working-class solidarity, cultural identity, and real social bonds still existed—but that past wasn’t untouched by ideology either.

- Was Britain ever truly unified? Or was it already fractured in ways Morrissey chooses to overlook?

- Was working-class solidarity ever free from the contradictions of capitalism? Or is this just another idealized construction of the past?

Is Glamorous Glue Also About Morrissey’s Own Nostalgia?

If the song critiques how Britain is held together by capitalist myth-making, it could also be subconsciously exposing how Morrissey’s own nostalgia operates the same way.

- He rejects the nationalist myth of Empire, but doesn’t he create his own myth of working-class England?

- If “glamorous glue” is the illusion that holds a broken nation together, isn’t his vision of a pre-Thatcher Britain also a kind of glamorous glue?

Morrissey might not intend for Glamorous Glue to critique his own nostalgic longing—but in doing so, the song highlights the danger of all nostalgia, even leftist nostalgia.

Morrissey’s Nostalgia as a Political Dead End

If nostalgia is always a fantasy that sustains ideology, then even progressive nostalgia can be limiting.

- If we only long for the past, we don’t imagine new structures beyond capitalism.

- If we only mourn what was lost, we risk trapping ourselves in a cycle of disillusionment instead of creating something new.

- If Britain was always dying, then what is there to reclaim?

This is why Glamorous Glue is so powerful—it’s not just critiquing capitalism—it’s mourning something that may have never existed in the first place.

Conclusion: Nostalgia and the Impossible

At its core, Morrissey’s nostalgia might be less about reclaiming a real Britain and more about mourning the impossibility of what Britain could have been. It’s a desire for something that never fully materialized, a longing for an alternative history that was never allowed to happen.

We’ll Let You Know (1992): Mediating National Identity Through Fantasy

We’ll Let You Know is one of Morrissey’s most haunting and prophetic songs—an elegy for a world where fantasy was once mediated by real life but has now been replaced by images, media, and empty spectacle.

By the time this song was released in 1992, British culture had already begun severing itself from real social bonds. The industrial working-class communities that once formed the backbone of English identity had been dismantled by Thatcherism, leaving behind a void where identity, purpose, and desire once existed.

In We’ll Let You Know, Morrissey sings not just about the decline of national identity, but about the existential consequences of losing fantasy as a function of real life.

You wonder how

We’ve stayed alive ’til now

We’ll let you know

We’ll let you know

But only if you’re really interested

In the past, fantasy was tied to real life. Even in the bleakest of circumstances, people dreamed of a better future—not just through entertainment, but through real, material struggle.

But now, fantasy no longer emerges from lived experience—it is dictated entirely by the media. The possibility of transformation, rebellion, or an alternative future is replaced by mass-produced imagery, empty distractions, and a culture of passive spectatorship.

The line “But only if you’re really interested” also drips with sarcasm and defeat. It suggests that most people aren’t interested in the truth—they’d rather stay plugged into the fantasy.

From Real Fantasy to Media-Controlled Desire

In earlier times, fantasy was essential for survival—a way to keep desire alive, to avoid the Real of death. Working-class communities, despite their hardships, sustained themselves through collective dreams of a better future, political change, or even small personal victories.

But now, fantasy has been hijacked.

- People no longer dream their own dreams—they dream what they’re told to dream.

- Desire is no longer self-generated—it is manufactured, commodified, and sold back to us.

- Instead of engaging in real material relationships, people engage with screens, celebrity culture, and nationalist nostalgia as a substitute for actual community.

And it has only gotten worse since 1992.

- The mass media that Morrissey was critiquing in the early ‘90s has since evolved into social media, algorithmic consumption, and hyper-curated digital realities.

- The destruction of local, social bonds that Morrissey mourns has only accelerated, leaving people more alienated, isolated, and unable to connect with anything real.

- Where once fantasy sustained desire, now it only represses it, pacifies it, and redirects it toward consumption.

A Nationalism of the Abandoned

While We’ll Let You Know is drenched in melancholy, it also carries a subtle undercurrent of nationalist longing—not in the sense of imperial pride, but in mourning a Britain that once had a real social fabric.

It’s no coincidence that the song touches on themes of football hooliganism, male camaraderie, and English pride. Morrissey isn’t celebrating these things—he’s diagnosing them.

- In the absence of real meaning, people will cling to whatever identity is available to them.

- When workers lose their jobs, their unions, their sense of community, all that’s left is cheap nationalism, sports rivalries, and cultural resentment.

- Nationalism, in this context, isn’t about power or strength—it’s about desperation, about filling the void left by the collapse of real material life.

This is the paradox of late-stage nationalism: the more a nation loses its real identity, the more its people cling to a fake, media-fueled version of it.

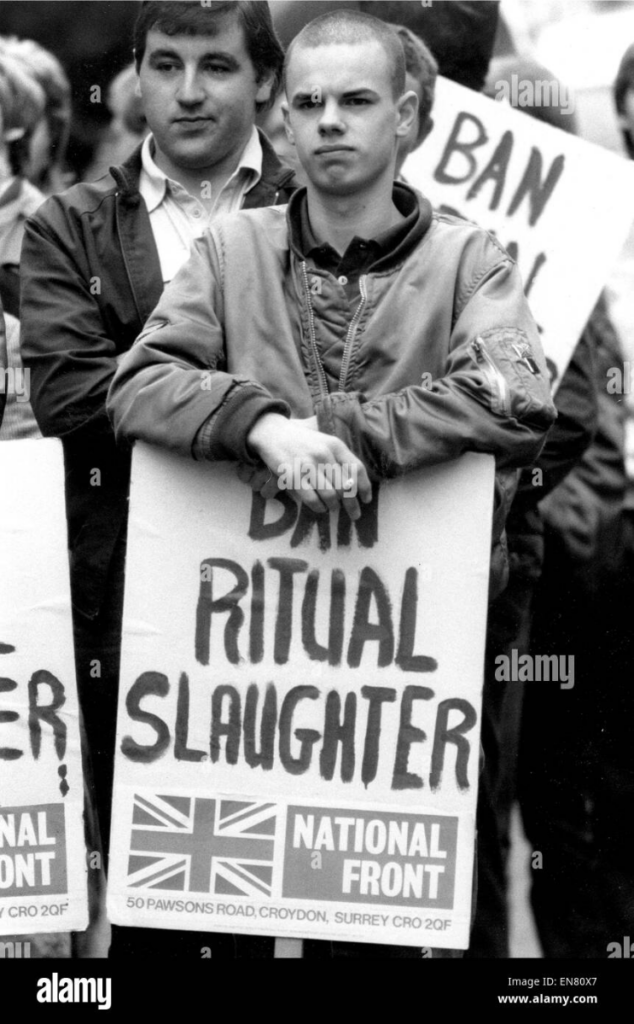

The National Front Disco (1992): Belonging and the Allure of Extremism

Few songs in Morrissey’s discography are as controversial, misunderstood, and uncomfortable as The National Front Disco. Released in 1992, it deals directly with the seductive pull of nationalism, the way identity is formed through exclusion, and the social and material rituals that reinforce belonging.

The genius of The National Front Disco lies in its refusal to moralize—it simply presents the ideological mechanisms that drive people toward extreme identity politics.

Rock Against Communism and the National Front Connection

One possible inspiration for the song comes from Rock Against Communism (RAC)—a movement that, despite its name, wasn’t about music at all, but about embedding white nationalist ideology into British subcultures. The RAC scene emerged in the late ‘70s and ‘80s, a direct reactionary response to leftist punk movements like Rock Against Racism.

Morrissey seems to be engaging with this historical moment, exploring how a young person—like David, the song’s protagonist—might get pulled into these movements.

But The National Front Disco isn’t just about one person’s descent into fascism—it’s about how all ideological identities operate, from punk to Marxism to nationalism.

The Paradox of Identity: Inclusion and Exclusion

One of the most striking things about nationalism, especially its extremist forms, is that it relies on both inclusion and exclusion at the same time.

- To belong to a nationalist movement, you must define yourself against an “other.”

- To maintain group unity, you must constantly reinforce who is and isn’t allowed in.

This same ideological trap ensnares not just nationalists but also modern punks and self-proclaimed “Marxists”. Many people treat punk and Marxism not as tools for changing material conditions, but as identities to maintain.

- Punk stops being about rebellion—it becomes a uniform (“a smelly uniform”), a performance, a subculture to belong to.

- Marxism stops being about revolution—it becomes a label, a set of aesthetics, a club.

David isn’t the only one getting trapped—everyone who prioritizes identity over action falls into the same cycle.

Nationalism is Fun

One of the most overlooked aspects of The National Front Disco is that it highlights something people rarely admit: extremist movements are fun.

“You want the day to come sooner, when you settle the score.”

This isn’t just a political transformation—it’s an emotional and social one. David isn’t becoming a nationalist because he’s reading obscure political theory—he’s hanging out, making friends, and having a good time.

Nationalist groups aren’t strictly political entities—they are social clubs, cultural movements, and communal spaces.

- They throw parties.

- They create rituals.

- They reinforce their identity through shared experiences.

This is why nationalist movements are so difficult to counter—because people don’t just engage with them on a political level, but on a deeply personal and emotional one. It’s the same reason why punk scenes, leftist groups, and activist movements can become insular, performative, and cult-like.

Nationalism, like any other ideology, is reinforced through material rituals of inclusion.

South Park, the KKK, and Rituals of Belonging

There’s a dark absurdity to all of this, which South Park captured perfectly in an episode where Uncle Jimbo and Ned infiltrate a KKK meeting. Instead of focusing on ideology, they find:

- A bake sale.

- A game of “Who’s wearing the craziest thing under their robes?”

- The Klan being regular dudes hanging out.

This isn’t just a joke—it’s a perfect representation of how identity politics operates. It’s not just about hatred; it’s about community, fun, and the feeling of belonging.

The same logic applies to David—his radicalization isn’t just about politics, it’s about having a group to be part of.

Why Does Morrissey Refuse to Condemn David?

One of the reasons The National Front Disco remains so controversial is that Morrissey never explicitly condemns David. The lyrics aren’t from an all-knowing, morally superior narrator—they’re from someone watching helplessly as a friend or loved one drifts into extremism.

“David, the wind blows, the wind blows”

Bits of your life away”

- There’s no anger—only resignation.

- There’s no political rhetoric—only melancholy.

- The song isn’t about fixing David—it’s about losing him.

In a way, Morrissey is acknowledging the larger systemic failure. If someone like David can be radicalized, it’s not just his fault—it’s the fault of a world that didn’t give him anything better.

Conclusion: The National Front Disco as a Warning

The National Front Disco doesn’t tell us what to do, but it forces us to confront an uncomfortable truth: People don’t join extremist movements because they’re evil.

They join because they need identity, community, and belonging. If the left, or any other alternative, can’t provide that—the far right will. And that’s why the song is so unsettling—because it isn’t about David. It’s about all of us.

I Know It’s Gonna Happen Someday (1992): Hope Before the Fall

In I Know It’s Gonna Happen Someday, Morrissey does something rare: he allows himself to believe in the possibility of change.

Released in 1992, before the co-optation of hope by New Labour and before the disillusionment that would define Maladjusted, the song presents a fragile but genuine optimism—a belief that something better is coming.

Hope Before Its Co-Optation

By 1992, Britain had spent over a decade under Thatcherism. The country had been hollowed out—industry dismantled, unions broken, working-class communities left to rot. The sense of collective identity that had once defined Britain was disintegrating.

Yet, in I Know It’s Gonna Happen Someday, there’s a glimmer of belief that this state of affairs is temporary.

My love

Whereverever you are

Don’t lose faith.”

This isn’t just personal hope—it’s collective, societal hope. Morrissey, for a moment, allows himself to believe that there will be a reversal, that Thatcherism will not define Britain forever. But there’s a melancholy underneath it—an unspoken fear that this hope might be misplaced.

New Labour and the Theft of Optimism

Fast forward just a few years, and hope did come—or at least, it seemed to.

- Tony Blair and New Labour swept into power in 1997, promising an end to Conservative rule, economic despair, and cultural stagnation.

- The working-class optimism that songs like I Know It’s Gonna Happen Someday expressed was harnessed for political gain.

- But instead of a real transformation, we got corporatized progressivism—a Labour Party that abandoned socialism for neoliberal centrism.

What I Know It’s Gonna Happen Someday didn’t predict was that hope itself would become a product, a brand, a marketing campaign.

The Edges Are No Longer Parallel (1997): Rejecting Political Salvation

By 1997, the hope that once flickered in I Know It’s Gonna Happen Someday had collapsed into disillusionment. The Edges Are No Longer Parallel is a direct response to that collapse, a realization that the structures that once seemed clear-cut—left vs. right, progress vs. stagnation—had blurred into something unrecognizable.

The title itself is a perfect metaphor: the lines no longer align, the path forward is no longer obvious, and political reality refuses to fit into the categories it once did. This isn’t just frustration with politics—it’s a deeper existential crisis about the entire system itself.

By 1997, New Labour had won a historic victory, ending 18 years of Conservative rule. Tony Blair had positioned himself as the leader of a new, modern Britain, selling a progressive vision that captured the optimism of the time. But Morrissey—always skeptical—wasn’t fooled.

The problem wasn’t just that Blair wasn’t truly progressive—it was that he was a symptom of a larger system where all political movements, no matter how radical their rhetoric, eventually get absorbed, diluted, and used to maintain the status quo.

My only mistake is I’m hoping

This line is devastating. It’s not just about personal regret—it’s a philosophical rejection of hope itself.

Žižek, Fantasy, and Embracing Hopelessness

This moment in Morrissey’s career aligns with Žižek’s concept of embracing hopelessness—not as a form of despair, but as a way to escape ideological traps. Žižek argues that hope often functions as a fantasy that prevents real change.

- If we hope that political leaders will bring progress, we remain passive, waiting for someone else to change things.

- If we hope that the system will reform itself, we ignore the reality that it is designed to sustain itself.

- Hope keeps us trapped—it convinces us that things will improve just because they should, rather than forcing us to accept that nothing changes unless it is forced to change.

Morrissey’s break after Maladjusted suggests that he was beginning to realize this.

Instead of investing in traditional political power, he moved away from faith in systems and toward something deeper—a psychoanalytic engagement with identity, nationalism, and the structure of desire. This shift explains his later, controversial support for the nationalist For Britain party.

For Britain, Trump, and Using the System’s Logic Against Itself

Morrissey’s support for For Britain wasn’t just reactionary—it was a rejection of mainstream political parties.

- For Britain wasn’t tied to the establishment—it functioned outside the dominant left/right binary.

- Just as Trump exploited the contradictions of the U.S. system, Morrissey saw nationalism as a tool that could be used against itself.

His thinking wasn’t that different from the logic of left-wing populism:

- If progressives actually joined nationalist parties, they could reclaim British identity from the far-right.

- If political leaders don’t follow the will of their supporters, they will lose power.

- Rather than rejecting nationalism outright, progressives could use it to dismantle the very structures it was meant to uphold.

This is where The Edges Are No Longer Parallel becomes prophetic—it’s about what happens when people realize that mainstream politics cannot save them. Morrissey saw that the old categories—left vs. right, socialist vs. conservative—no longer applied.

Beyond Traditional Politics: Toward the Psychoanalytic

If Maladjusted was Morrissey’s final engagement with “traditional politics”, then his break afterward marks his deeper move into psychoanalytic themes. This transition mirrors something fundamental:

- Traditional politics always gets co-opted—radical movements get absorbed, leaders compromise, and revolutions become brands.

- The only way to truly challenge ideology is to understand the structure of desire itself.

Morrissey, whether consciously or not, seems to recognize this. His work after Maladjusted shifts toward a deeper interrogation of identity, nationalism, and the ways people seek belonging—which I’ll explore in another post.

For now, The Edges Are No Longer Parallel remains a crucial turning point: the moment when Morrissey stopped believing in political solutions altogether.

Irish Blood, English Heart (2004): A Nationalism That Rejects Nationalism

Unlike some of Morrissey’s more ambiguous songs, Irish Blood, English Heart lays its themes out plainly, bluntly, and unapologetically. It’s a declaration of disillusionment with the political establishment, a rejection of the shame and contradictions of English identity, and a plea for a nationalism that isn’t rooted in exclusion, empire, or reactionary nostalgia.

It’s also one of Morrissey’s most misunderstood songs—not because its meaning is hard to grasp, but because people don’t want to acknowledge the contradictions at the heart of national identity.

I’ve been dreaming of a time when

To be English is not to be baneful

To be standing by the flag not feeling shameful

Racist or partial

These lines cut straight to the core of the problem:

- To be English is to carry the weight of colonialism, class oppression, and empire.

- To stand by the Union Jack is to inherit centuries of violence, conquest, and exploitation.

- The progressive response to this has often been to reject Englishness entirely—to see patriotism as inherently reactionary, racist, or imperialistic.

But Morrissey doesn’t want to reject Englishness. He wants to redefine it.

He dreams of a time when English identity isn’t synonymous with historical guilt, when people can reclaim their national identity without it being poisoned by its past. This is the same ideological move he flirts with in The National Front Disco—the idea that nationalism doesn’t have to belong to the right-wing.

The Absolute Rejection of the Political Establishment

I’ve been dreaming of a time when

The English are sick to death of Labour and Tories

This is where Morrissey’s anti-establishment stance fully crystallizes. By the time this song was released in 2004, Britain had already experienced:

- The failure of New Labour—Blair’s government, which had abandoned working-class politics for neoliberal centrism.

- The continuation of Tory elitism—the same class-driven politics that had dominated Britain for decades.

Morrissey isn’t calling for a new party or a different leader—he’s saying that the entire political system is rotten. This is why his later support for outsider movements (like For Britain) isn’t as surprising as people pretend it is. His frustration isn’t about left vs. right—it’s about the fact that traditional politics always leads to the same outcome.

Irish Blood, English Heart – The Duality of Identity

The song’s title itself is a contradiction:

- Irish Blood – A history of colonial oppression, British rule, and the struggle for independence.

- English Heart – A cultural identity that, despite everything, Morrissey still belongs to.

This is the paradox of English nationalism: it is a nation that both oppressed and was oppressed, a country that built an empire yet abandoned its own working class. Morrissey embodies this contradiction—an Englishman of Irish descent, someone who both hates what Britain has done and still dreams of something better.

This is why Irish Blood, English Heart feels both defiant and mournful. It isn’t a patriotic anthem, but it also isn’t a rejection of Englishness. It’s a search for a national identity that isn’t defined by either guilt or conquest.

Conclusion – A Nationalism of the Betrayed

Irish Blood, English Heart is a song about longing for an identity that doesn’t exist. Morrissey wants an England that isn’t defined by its past sins, a politics that isn’t controlled by the ruling class, and a nationalism that isn’t racist, reactionary, or exclusionary.

But that England never came. Which is why, like so many of Morrissey’s songs, Irish Blood, English Heart ends not with a resolution, but with a dream. Because that’s all that’s left.

My Love, I’d Do Anything for You (2017): Recognizing Ideology

Morrissey has always been suspicious of authority, but My Love, I’d Do Anything for You elevates that suspicion into a direct attack on ideological control. This is not just a love song—it’s a manifesto, a warning, and a plea to wake up to the structures that shape our lives.

More than any other song in his later discography, My Love, I’d Do Anything for You is about the necessity of ideological recognition—of understanding that our thoughts, beliefs, and desires are not as freely chosen as we assume.

Teach your kids

To recognize and despise all the propaganda

Filtered down

By the dead echelons of mainstream media

This is Morrissey at his most direct, spelling out what many of his songs have implied:

- We do not live in a world of neutral information. Everything we consume—news, entertainment, advertising, even education—is filtered through ideological structures.

- Mainstream media doesn’t just report facts—it shapes reality, defining what is and isn’t worth talking about.

- The “dead echelons” refer to the ruling class, the entrenched establishment that no longer needs to actively deceive people because the system itself sustains the illusion of choice.

This mirrors Žižek’s view on ideology—it isn’t just propaganda in the classic sense; it’s the very framework through which we understand the world. We don’t recognize ideology because we are inside it.

Morrissey is saying: Teach your kids to see it. Because if they don’t, they will live their lives mistaking their cage for freedom.

Society’s Hell – The Illusion of Individualism

You know me well

My love, I’d do anything for you

Society’s hell

You need me just like I need you

At first, this section feels personal, like a romantic confession. But it’s also a critique of the false promises of individualism.

- “Society’s hell” – Not because of any one policy or government, but because we are trapped in a structure that presents itself as freedom while controlling every aspect of our lives.

- “You need me just like I need you” – Human connection is the only real escape, the one thing that cannot be fully commodified.

This echoes the Frankfurt School’s critique of capitalism—that modern life isolates people, making them believe they are autonomous individuals while keeping them dependent on systems that exploit them.

Morrissey, in his usual fatalism, isn’t offering a way out—he’s just acknowledging that the system is rigged.

The Boredom of Modern Life

Weren’t we all

Born to mourn and to yawn at the occupations

That control

Every day of our lives we can’t live as we wish

Live as we wish, live as we wish

This is the most devastating part of the song—because it exposes the deepest ideological trick of all.

- We are told to pursue careers, to work, to contribute.

- We believe that this is just how life works, that there is no alternative.

- But what if we were never supposed to live this way?

“Born to mourn and to yawn” suggests that life under capitalism is fundamentally joyless, repetitive, and predetermined.

- Work is not about fulfillment—it’s about control.

- Even rebellion is pre-absorbed into the system—punk, counterculture, even “alternative” politics are marketed back to us as lifestyle choices rather than genuine movements.

And the worst part? Even if we recognize this, we are still trapped inside it. Morrissey repeats “Live as we wish” as if trying to will it into existence—but it’s clear that we don’t, and maybe never will.

Conclusion – Seeing the Cage Doesn’t Mean You Can Leave It

My Love, I’d Do Anything for You is not a hopeful song. It doesn’t offer solutions, revolutions, or alternatives—it just tells the truth: The system is built to control you. Your thoughts are not entirely your own. Even the belief that you are free is part of the illusion.

Recognizing this isn’t an escape, but it’s the first step. And Morrissey’s final message? At the very least, don’t let your kids grow up blind to it.

I Wish You Lonely (2017): The Machinery of Nationalist Sacrifice

In I Wish You Lonely, Morrissey delivers one of his most biting critiques of nationalism—not just as an ideology, but as a system of sacrifice. Unlike Irish Blood, English Heart, which seeks a nationalism free from shame, this song fully dismantles the way nations manufacture meaning through death.

Morrissey isn’t just questioning why people die for their country—he’s asking why this kind of sacrifice is glorified, ritualized, and endlessly repeated.

The Power of Nationalism – Worship Through Death

Nationalism’s greatest strength is its ability to make people willingly die for it.

Tombs are full of fools who gave their life upon command

Of monarchy, oligarch, head of state, potentate

And now never coming back, never coming back

This is a direct rejection of the “heroism” that nations build themselves upon:

- War memorials, national holidays, history books—they all turn soldiers into sacred figures, framing their deaths as glorious, necessary, and noble.

- In reality, most of these deaths serve no real purpose. They happen at the command of elites—monarchs, politicians, corporate interests—people who themselves never risk anything.

- The dead don’t return. They don’t get to see whether their sacrifice was worth it. They are gone, and their memory is used as fuel for the next generation of recruits.

This is what nationalism does best—it doesn’t just kill, it mythologizes death to ensure that more will follow.

Nationalism as an Emotional Machine

Nationalist ideology isn’t purely rational—it is deeply emotional, symbolic, and ritualistic.

- Nations do not just ask people to fight—they make it a moral duty, a spiritual calling.

- If someone questions a war, they are told they are dishonoring the dead—as if the greatest disrespect isn’t sending people to die in the first place.

- Death cements identity—a nation that loses its soldiers is compelled to avenge them, creating an endless cycle of war, mourning, and more war.

This is why war monuments exist—not just to remember the dead, but to ensure that people keep dying.

- Would people still die for their country if their sacrifice wasn’t framed as noble?

- If war memorials were statues of decaying corpses, shattered bones, and sobbing families, would young men still enlist?

- Nationalism relies on beauty to mask horror.

Morrissey sees through this and refuses to participate.

The Absurdity of National Sacrifice

Another layer of irony in this song is that the same people who fight and die for their country often receive nothing in return.

- Veterans are discarded.

- The wealthy elite benefit from wars, but never fight in them.

- The poor and working class are sent to die, while the ruling class profits, writes history, and moves on.

This is the ultimate nationalist scam:

- You are told your country needs you—but the people who run the country don’t need you at all.

- You are told you will be honored in death—but only if your death can be used to inspire more.

Conclusion – A Rejection of the Nationalist Death Cult

I Wish You Lonely is not just anti-war—it’s anti-nationalist in the deepest sense. It exposes nationalism for what it truly is:

- A machine that turns death into meaning.

- A system that convinces people to give their lives away for nothing.

- A loop that never ends because the dead cannot object to how their memory is used.

Morrissey’s final verdict? Let the tombs be full of fools—but let us not join them.

Jacky’s Only Happy When She’s Up On The Stage (2017): Nationalism as Performance

Jacky’s Only Happy When She’s Up On The Stage is one of Morrissey’s most brutal and precise dissections of nationalism as a symptom rather than an ideology.

Jacky is not a true believer—she is a performer, someone who has experienced a traumatic rupture with the Real and now clings to nationalism not out of conviction, but as a coping mechanism. She doesn’t believe—she acts as if she believes.

She is determined to prove

How she can build up the pain

Of every lost and lonely day

Jacky’s nationalism doesn’t emerge from a rational ideology—it emerges from pain, loss, and a fundamental lack.

- She has experienced a rupture, an encounter with the Real—something too overwhelming, too traumatic, too destabilizing to confront directly.

- Instead of dealing with it, she performs a new identity, covering the wound with rituals, spectacle, and politics.

- She builds up the pain into something public, visible, theatrical—because if she lets herself stop performing, she might have to face what she’s really missing.

This is the function of ideology in psychoanalysis—it is never just about belief, but about filling a void, covering up an unbearable truth.

Racism as a Performance of Identity

Cue lights! I am singing to my lover at night

Scene Two: Everyone who comes must go

Scene Four: Blacker than ever before

Scene Six: This country is making me sick

The structure of this verse mimics a theatrical production—a series of acts, not spontaneous beliefs. Jacky’s nationalism isn’t deeply felt—it’s scripted.

- Her racism isn’t organic—it’s performative, a way to align herself with a group that gives her an identity.

- Blaming immigrants, racial minorities, or outsiders is an easy way to redirect her pain outward, rather than looking inward.

- The phrase “Blacker than ever before” isn’t just a racial reference—it’s a description of Jacky’s own state of mind—she is growing darker, more consumed by this performance.

- By the final scene, she can’t sustain it anymore—“This country is making me sick”—her nationalism, instead of healing her, has become overwhelming.

Nationalism, like any ideology, can provide temporary jouissance—a kind of perverse enjoyment—but eventually, it breaks down under its own contradictions.

The Big Other, Sexual Neglect, and Nationalism as a Symptom

Jacky cracks when she isn’t on stage

See the effects of sexual neglect

Here’s the core of the problem—Jacky’s nationalism is not about politics but about desire.

- She doesn’t know what she wants.

- Instead of confronting this void, she projects her frustration outward.

- Nationalism, like many ideological structures, becomes a substitute for real desire, a way to experience jouissance without having to deal with her own lack.

This is why nationalism is so effective. It is not just a belief—it is a way to channel anxiety, frustration, and sexual repression into a structured, socially acceptable form.

No script, no crew, no auto-cue

No audience telling her what to do

Exit, exit

Once Jacky can no longer perform, she collapses.

- She can only function if there is an audience, a narrative, an external confirmation of her role.

- When that is taken away, she is left alone with herself—and that is unbearable.

- Her final words—“Exit, exit”—suggest an end, a breakdown, an inability to continue without the ideological fantasy sustaining her.

Conclusion – Nationalism as a Failed Substitute for Desire

Jacky is not a monster. She is not an ideologue, not a true believer, not even a nationalist in the deepest sense. She is a person who has lost something fundamental—love, meaning, identity—and is trying to fill that void through performance.

Nationalism, for her, is not a solution—it is a symptom.

But, as the song makes clear, symptoms do not last forever. The moment Jacky stops performing, she collapses. And this is the hidden truth of nationalism: It isn’t real. It’s just a stage play that people put on to distract themselves from what they’re really missing.

Is Progressive Nationalism a Dead End?

Nationalism, and even the discourse around immigration, operates at the level of jouissance—a way to avoid confronting the Real of economic exploitation.

Rather than addressing the structural forces that create displacement, economic instability, and ecological collapse, the debate around immigration becomes a ritualized ideological performance, where both sides engage in a fantasy that sustains the system rather than challenging it.

This is what makes progressive nationalism a dead end—not because its intentions are bad, but because it still operates within the system’s logic rather than outside of it.

Nationalism and Immigration as Ideological Escape Routes

Morrissey, in his typical way, is not making a simplistic argument against immigration—he’s forcing us to ask what mass immigration actually means within the system’s internal logic.

- People don’t want to leave their homes—immigration is rarely an individual’s first choice but is instead the product of economic collapse, war, and climate crisis.

- The same nations that fuel the global crisis—through imperialist foreign policy, corporate exploitation, and environmental destruction—position themselves as the saviors, granting or denying access to displaced people.

- This creates an identity crisis—a rupture between belonging and dependence. Immigrants are told they should assimilate, yet they are also reminded that they are outsiders, guests in a country that is doing them a “favor.”

This is where jouissance comes in—the entire immigration debate becomes a way to avoid acknowledging the brutal economic reality of the situation.

Rather than confronting why people must migrate, both nationalists and progressives focus on the symbolic aspects of immigration—assimilation, national identity, cultural clashes—while the actual material causes remain untouched.

The Spiral of Death: How Ideology Reinforces Itself

People don’t want to leave their homes, but they’ll become dependent on the acceptance of the very nations that accelerated the problem, causing an identity crisis/rupture–which will likely lead to more extremism.

And more extremism will lead to more ideological siloing in a Spiral of Death. This is the inevitable trajectory of the system as it stands:

- Climate change, economic exploitation, and war create displacement.

- Displaced people migrate to countries that were complicit in their displacement.

- These countries experience a rise in nationalism and reactionary extremism.

- In response, ideological polarization increases, leading to more extremism on all sides.

- The core issue—economic and environmental exploitation—remains untouched.

This cycle will only intensify as climate change accelerates. The Real of ecological collapse will force millions more people into displacement, making immigration not just a cultural or political issue but an existential one.

The problem? Ideological polarization makes true systemic change impossible.

- Progressives and reactionaries play their respective roles in the immigration debate, each reinforcing the other’s existence.

- The left defends immigration as a moral imperative without addressing the economic systems that create displacement.

- The right attacks immigration as a threat while ignoring the historical and economic forces that caused the crisis in the first place.

- Both sides sustain the illusion that the problem is about borders, identity, and culture—rather than about capital, resources, and global power.

This Spiral of Death continues because it is useful—to politicians, to corporations, to media outlets, and to those who benefit from ideological division.

Morrissey’s Challenge: See Through the Illusion

If systemic change is possible, people need to understand how ideology functions in their everyday lives. The system relies on ritualized ideological battles—whether it’s over immigration, race, or nationalism—to keep the focus away from its fundamental economic contradictions. On Neal Cassady Drops Dead, Morrissey presents this as a choice:

Victim, or life adventurer

Which of the two are you?

This isn’t just a personal question—it’s a structural one.

- Do you accept your ideological role in the cycle?

- Or do you recognize the mechanisms at play and refuse to participate in the fantasy?

Nationalism, in any form, is ultimately just another symptom—a way to channel frustration into something manageable rather than addressing the Real of systemic collapse.

So yes—progressive nationalism is a dead end. Because all nationalism is a dead end. The system isn’t broken—it’s designed to function this way. And until that is recognized, nothing changes.

But that doesn’t mean change is impossible. It just requires a different type of engagement with our real material conditions, and Morrissey provides us lots of lessons in how to approach this, which we’ll explore soon…