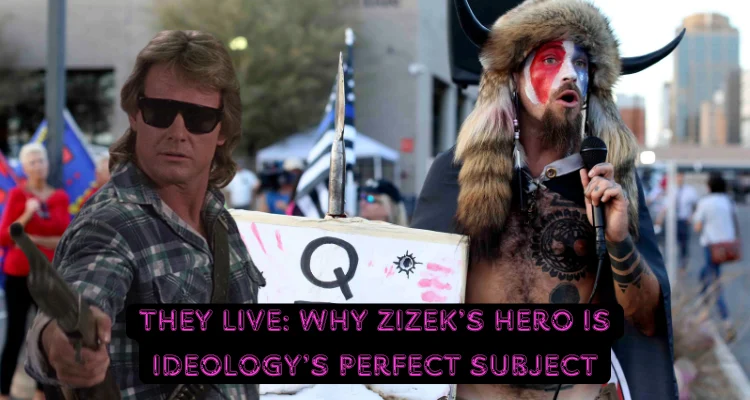

Slavoj Žižek famously interprets They Live (1988) as a brutal metaphor for ideological awakening. In his reading, the film’s six-minute alleyway brawl—where Nada tries to force Frank to wear truth-revealing sunglasses—captures the trauma of recognizing ideology’s grip on reality. The fight is long, Žižek says, because truth hurts.

But what if They Live isn’t about discovering the truth at all?

Rather than peeling back capitalist illusion, the film chronicles a descent into a new, equally ideological fantasy—driven not by clarity, but by psychosis, pleasure, and a desperate search for meaning. Nada doesn’t escape ideology; he trades one symbolic frame for another. The supposed “truth” of the glasses offers a simpler fantasy: enemies are now visible, the world is legible, and he’s the hero.

The fight scene isn’t about disillusionment—it’s about conversion. Frank resists because he still has something to live for. Nada, having lost all ties to the old symbolic order, clings to a narrative that feels intense, emotional, and satisfying. Žižek misses this emotional and racial subtext. He flattens the film into a universal story of awakening, overlooking how ideology functions not just as illusion, but as excitement, belonging, and narrative coherence—especially for those who feel left behind.

From Good Boy to Dissident: Nada’s Radicalization

Nada begins as the ideal subject of Reagan-era ideology: hardworking, religious, individualist. He believes in the system, even if it’s failed him. But his symbolic world quickly collapses. Jobs vanish. Religion offers no answers. Police destroy the shantytown he’s begun to call home. As one homeless man says, “It’s just people afraid to face the future.”

That future isn’t just economic uncertainty—it’s the terrifying void left when ideology disintegrates. The collapse of the symbolic order exposes the subject to what Lacan would call the Real: the raw, structureless chaos of existence, including death, meaninglessness, and the fundamental impossibility of wholeness. In this space, anxiety thrives. Without a stable fantasy to organize experience, Nada is left unmoored—confronting the Real directly, and unable to bear it.

But ideology rushes in to cover that void. The sunglasses don’t offer truth. They foreclose anxiety by providing a narrative scaffold—a new symbolic frame in which Nada is righteous, legible, and necessary. He isn’t waking up. He’s clinging to the jouissance of ideology: the excessive enjoyment of certainty, of action, of moral clarity. It’s not that ideology tricks him—it saves him from the terror of symbolic collapse. What looks like revolution is closer to a psychotic defense, a way to hold the world together through intensity and belief.

This mirrors modern screen-based radicalization. QAnon believers, punks, anti-vaxxers—none of them reject ideology entirely. They reject a symbolic order that no longer gives them meaning and replace it with one that does. The enemy changes, but the structure stays the same. Like Nada, they don’t wake up. They just change dreams—and cling to them with fervor, because the alternative is collapse.

The Glasses: Ideology for Ideology

Žižek treats the sunglasses as a metaphor for exposing ideological illusion. But the glasses don’t reveal truth—they restructure desire. They don’t expose reality; they give it form, coherence, and intensity.

Through them, the world becomes simplified: human vs. alien, us vs. them. This binary is emotionally satisfying because it transforms confusion into clarity and personal failure into righteous anger. The glasses aren’t a break from ideology—they’re a more compelling version of it. More vivid. More direct. Easier to follow.

The aliens are coded not just as elites but as outsiders—foreign, parasitic, and shown occupying positions of media, finance, and power. While the film doesn’t explicitly frame them through race or ethnicity, its logic mirrors familiar patterns of scapegoating—especially Nazi Germany’s portrayal of Jews as manipulative overlords corrupting society from within. Like Germany post-WWI, Nada is economically discarded and symbolically disoriented. The world no longer makes sense. The glasses don’t fix that. They assign blame.

This isn’t truth. It’s ideological compensation—designed not to clarify but to locate blame. Just as the Nazis offered a fantasy of renewal through purification, They Live offers Nada a fantasy of moral clarity and violent redemption. Ideology doesn’t fade. It sharpens.

And like the Nazis, Nada’s ideology is obsessed with purity. Once he puts on the glasses, his violence becomes selective. He kills only aliens. Never humans. The split between “us” and “them” isn’t just epistemological—it’s moral, biological, existential. He doesn’t fight for liberation. He fights for cleansing.

Which is ironic—because the system he’s resisting isn’t upheld by aliens alone. Humans are complicit too. The elites, the sellouts, the silent bystanders—they all sustain the machine. But Nada’s new fantasy erases that complexity. The glasses don’t help him understand how power works—they give him permission to simplify it. In doing so, they turn a network of relationships into a racialized myth of invasion. His crusade isn’t against capitalism. It’s against contamination.

The Fight Scene: Coercion, Intimacy, and Racial Tension

The infamous fight is often seen as the painful gateway to ideological awakening. But it’s really about emotional coercion. Frank resists not because he’s blind to truth, but because he still has a life—family, routine, stability. His line, “I don’t bother them and they don’t bother me,” isn’t complicity—it’s survival.

Nada, having lost everything, needs someone to join him in the intensity of his new fantasy. The fight is less about convincing Frank and more about dragging him in. Like an addict begging someone to try the drug, Nada needs validation—needs someone to feel what he feels.

Race matters here. Frank, as a Black man, has far more to lose in aligning with a fringe, militant ideology. His refusal is rational. Nada’s coercion is reckless, emboldened by whiteness and desperation.

Once Frank puts on the glasses, they’re marked as enemies. Not for what they believe—but for stepping outside the symbolic order. The fight wasn’t painful because “truth” is hard. It was painful because ideology is intimate, and tearing someone into your delusion is messy.

Ideology is Exciting: Why Truth Isn’t the Goal

Ideology isn’t just comfort—it’s fun. It gives form to pain, purpose to alienation. Nada doesn’t act out of anti-capitalist clarity. He acts because the world through the glasses feels meaningful.

The sunglasses don’t lead to organization or strategy. They lead to vigilante spectacle. Destroy the transmitter. Kill the aliens. Win the war. It’s emotional release—not transformation.

This mirrors the logic of conspiracy communities, punk movements, even fringe politics. They’re often united not by coherent critique, but by the thrill of being “in on something.” Special knowledge becomes a shield against self-examination. Truth is too slow, too ambiguous. Ideology is fast, righteous, and fun.

Žižek’s error is treating the glasses as clarity when they’re really style—ideology with better lighting, cleaner enemies, and more exciting myths.

The Real Tragedy: Choosing Ideology Over Connection

Ironically, Nada had a chance to materially improve his life. The clean-shaven “sellout” homeless man offers him a way in—a means of survival, maybe even subversion. He’s not stuck in fantasy. He’s navigating ideology tactically.

Nada, by contrast, gives everything up for the symbolic purity of resistance. He had a job, shelter, even a friend. But he chose myth. And for that, he dies.

As Morrissey put it, “Tombs are full of fools who gave their life up on command.” Nada isn’t a martyr. He’s a man who obeyed a new symbolic law with the same blind faith he once gave to America. He didn’t break free—he just flipped the script. The transmitter is destroyed, but the system remains. Nothing changes.

Conclusion: Addiction, South Park, and Žižek’s Misreading

Nada didn’t escape ideology—he became its servant. His anti-alien crusade obeyed a new symbolic law that shaped his every move in relation to the system he thought he was resisting. In Lacanian terms, he never left the symbolic order—he just mirrored it in reverse.

This dynamic is brilliantly parodied in South Park’s Matrix parody, where characters “wake up” only to get drunk again because reality sucks. Like addiction, ideology gives the illusion of awakening while deepening dependency. The rush of revelation is just another high.

Ultimately, They Live doesn’t show us the trauma of waking up.

It shows us the tragedy of thinking you have—when all you’ve done is swap one fantasy for another.